ELENA AFIRMATIVA

Diagrammatic motherhood as a family visualization (2015–2025)

Murcia, July 28, 2015. Olivia Morgado López is born. In the same place, on August 1, 2017, Lucía Morgado López is born. Two apparently healthy girls enlarge our family. But when does motherhood begin, how much does it weigh, how tall is it, what does it feed on, how much does it cry, what shape does it take, how do I know if it is a healthy motherhood?

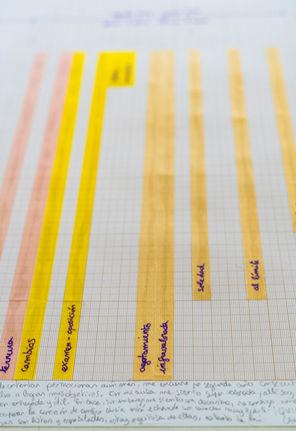

This project arises from a decade of motherhood and family changes, and, consequently, from the emotional transformations that have accompanied them. Since the birth of my first daughter in 2015, I have been developing a visualization of affective data that gathers different milestones which marked turning points in family life: the arrival of my second daughter, the illness of other family members, three moves, the adoption of two cats, the transition from the babies’ absolute dependence to the autonomy of girls who, perhaps prematurely, are already brushing up against adolescence. Each stage has entailed a reconfiguration of the affective network, a shift in the intensity of bonds, a new orientation in everyday life. All of this translates into emotional diagrams that raise colored columns made with translucent papers, whose height depends on the intensity of the emotion. Although in recent decades many artists have reflected from within their own motherhood, a decisive reference for me is Mary Kelly, especially her project Post-Partum Document (1973–1978). There, Kelly proposed, in her own words, “my lived experience as a mother and my analysis of that experience” (Kelly, 1983, p. 39). That double gaze—between the intimate and the analytical, between everyday life and symbolic construction—has served me as a critical horizon for thinking through my own work. In my case, this visualization was not initially conceived as an artwork, but as a vital need: a way of holding myself in the midst of the experience. What happened is that, in my life, art and the everyday have never been separate; rather, they dissolve into each other. For this reason, in both my life philosophy and my teaching and artistic practice, I always keep with me Robert Filliou’s premise: “Art is what makes life more interesting than art” (1984). These diagrams unfold on a 10-meter roll of Canson graph paper, of which I have worked approximately two and a half meters so far. The rest remains blank because my experience of motherhood and family is ongoing, changing, and there is still life to be explored. Thus, this roll—which began as a space for the introspection I could barely afford at the beginning, with no time, sleep-deprived, yet with the adrenaline of someone who realizes that, without intending it, she has entered a hiatus from public artistic production while nevertheless feeling more creative than ever—became a form of therapy, a visual travel diary of motherhood. In the center of the paper, the emotions are diagrammed; but this center has a neighboring zone, in friction—margins that allow for rereading and questioning the central emotional discourse. Those zones are the margins, where handwritten notes emerge: memories, invented words, songs, sentences that condense shared moments. The margin does not accompany as something secondary; it sustains other family discourses, more intimate and fragmentary, which complete and sometimes deflect the central axis. Writing on the edges is to acknowledge that family life is not narrated only from the center, but also laterally, from the multiple voices that constitute it. Kelly emphasized how the recourse to diagrams and a pseudo-scientific discourse in Post-Partum Document should not be understood as objective or authoritarian records, but as strategies to evoke “the sense of touch, so these signs invoke the sensuous, emotive quality of the mother’s lived experience” (Kelly, 1983, p. 41). In my practice, tactile experience becomes decisive: I cut and paste small slips of paper, I color grids, I write by hand. In my artistic life and in my motherhood, hands do everything; they are capable of materializing emotions and thoughts that language cannot infiltrate. To this emphasis on the tactile I add the work of contemporary artist Carmen Winant, for whom physical contact with the image is essential to the very process of creation. Winant collects physical photographs from diverse sources—many about motherhood/reproduction—and notes that through touch she discovers possible narratives and connections she would not see by looking alone. In her project My Birth (2018), for instance, she deploys thousands of found images of childbirth across walls, rubbing, reaffirming, reordering the surfaces as if they were bodies that demand to be touched. For Winant, touching is a way of understanding. This striking gesture reinforces my conviction that touch—the imprint of the hand, that direct friction with material—is not accessory: it is the core of diagram-thinking and maternal feeling in my work. Paper is the absolute protagonist here. It is a lightweight material that nonetheless bears the full weight of my motherhood, with its desires and frustrations. Although it had already played a leading role in many of my earlier artistic projects, on this occasion it has been the everyday medium available throughout my daughters’ childhoods: non-toxic, non-hazardous, and always at hand. Paper has allowed me to play, learn, and create with them. What began as an intimate, almost therapeutic gesture—a way both to order and disorder my mind by visualizing the present—now reveals itself as an artwork: a personal diagram-writing and an emotional landscape unfolded on a single surface that speaks of family and preserves the memory of a decade of motherhood in transformation. References: Kelly, M. (1997). Mary Kelly. Phaidon. Filliou, R. (1984). Dear Skywatcher: Art Is What Makes Life More Interesting Than Art. Sammlung Hoffmann, Berlin. Winant, C. (2018). My Birth. The Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA. Exhibition and artist’s statement.